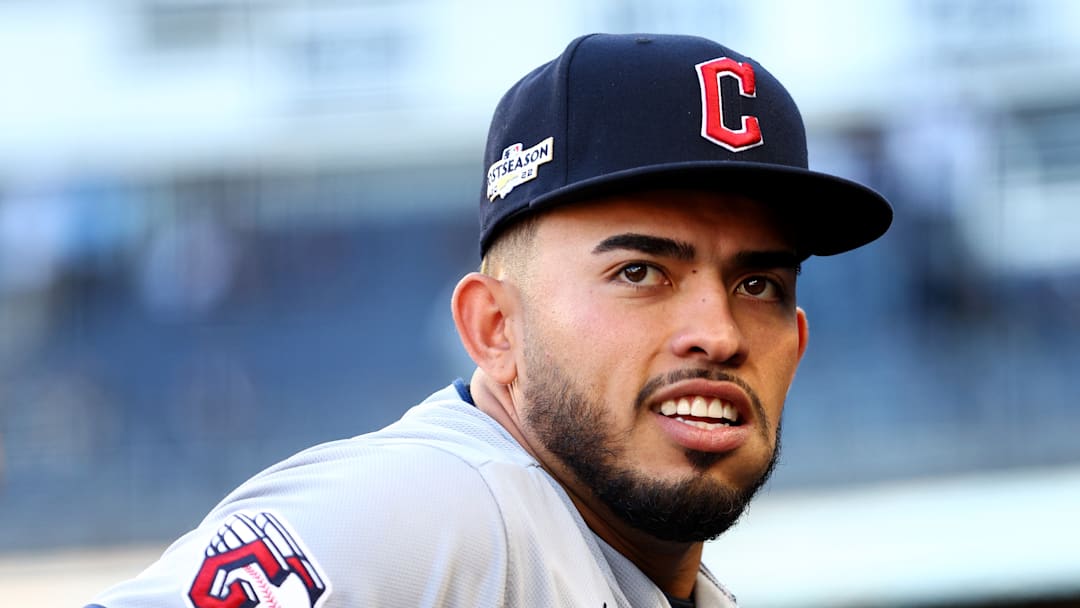

Guardians’ Joey Cantillo may be next development coup for a team that can train velocity

Akron RubberDucks pitcher Joey Cantillo (22) during an Eastern League baseball game against the Richmond Flying Squirrels on May 6, 2022 at The Diamond in Richmond, Virginia. (Mike Janes/Four Seam Images via AP)

By Zach Buchanan

Justin Baughman was going to give the kid one more shot.

For roughly a year, the Padres scout had ping-ponged between the Pacific Northwest and Hawaii to get a look at the island state’s top amateur prospects. And every time he’d seen left-hander Joey Cantillo, Cantillo had been … fine. At 6-foot-4 and 200 pounds, Cantillo was big. With his fastball coming in at 86 mph, his arm was not. Sometimes his command wavered. Sometimes he got hit. Rarely did he light up the radar gun.

Each look had left much to be desired, yet Baughman couldn’t quite push Cantillo from his mind. So he boarded a plane in the early spring of 2017 to sit behind home plate for one more start. What the veteran scout saw that day is burned in his mind. Cantillo threw two curveballs in the first inning, missing outside the zone with each. He never threw another breaking pitch the rest of the way. Using only his fastball, Cantillo struck out 18 batters in a seven-inning shutout. Hitters whiffed on his heater 32 times. The pitch was sitting 84-86 mph.

“It was the most dominant thing I’d ever seen,” Baughman says.

That summer, the Padres drafted the 17-year-old in the 16th round.

Six years later, Cantillo remains a well-kept secret. He’s pitched well at every stop of the minors, with a career 2.38 ERA as a professional. The fastball that flummoxed Hawaii high schoolers still darts over the top of minor-league barrels, even when it struggles to crest 90 mph. A split changeup dives below bats with a similar frequency. He’s added 25 pounds of lean muscle to his Division-I quarterback frame.

But most notably, Cantillo is throwing harder. Midway through the abbreviated 2020 season, the lefty was flipped to Cleveland as part of the package for starter Mike Clevinger, and it’s been a consequential change of scenery. Few organizations in baseball develop starters quite like the Guardians, and more specifically, rival scouts say few are as accomplished when it comes to developing velocity. Since joining Cleveland two and a half years ago, Cantillo has gone from sitting 89 mph to hitting 97 mph last spring. This past season with Double-A Akron, during which he posted a 1.93 ERA and struck out nearly 36 percent of his batters, he sat 92-95.

#Guardians 22yr old LHP prospect Joey Cantillo continues to mow people down for Double-A Akron. Cantillo strikes out 9 batters for the 3rd time this season and lowers his ERA to 2.03 on the year.

Line – 4.2(IP) 6H 2R 1ER 1BB 9SO@joeyycantillo @AkronRubberDuck #ForTheLand pic.twitter.com/x7vkGivnL3

— Guardians Prospective (@CleGuardPro) June 30, 2022

In most organizations, those numbers would generate a lot of hype. But with the Guardians, Cantillo has a lot of high-flying company. Four fellow Cleveland pitching prospects – Daniel Espino, Gavin Williams, Logan Allen and Tanner Bibee – rank in Baseball America’s top 100 prospects. Cantillo does not. In MLB Pipeline’s accounting of the Guardians’ system, Cantillo ranks just 22nd. When it comes to young, promising pitchers, Cleveland is loaded.

But if that means Cantillo is overlooked, it doesn’t make his development any less impressive or revealing. Six years ago, he was a soft-tossing former 16th-rounder with a good feel to pitch and not much else. Now, he’s on the 40-man roster, a legitimate starting pitching prospect with at least a league-average arm and a real shot to make his major-league debut in 2023.

“I heard a lot about Cleveland’s pitching development. At the time, I was like, ‘We’ll see,’” Cantillo says. “Now looking back, it’s like wow, what a monumental thing that was for me in my career.”

This is how to turn a guy into a dude.

If Cantillo had been throwing even 90 mph at age 17, Baughman thinks, the Padres may never have been able to draft him. In reality, San Diego had Cantillo all to itself. The Padres were the only team to invite Cantillo to a pre-draft workout, and they waited to draft him until the 16th round because they knew he’d last that long. For a signing bonus that was just a hair over $300,000, the light-tossing lefty was theirs.

For the first two years of his professional career, Cantillo focused not on velocity gains but only on getting outs. The Padres, he says, didn’t emphasize mechanical adjustments as much as performance, which was just fine with him. Always hyper-competitive — Cantillo’s high school coach tells stories of four-hour ping-pong marathons that were allowed to end only when Cantillo had claimed a victory — the lefty relished the opportunity to test his skills against other young prospects. In 2019, despite still throwing in the high 80s, a 19-year-old Cantillo managed a 2.26 ERA in roughly 110 innings across two levels of A-ball.

If he’d remained a Padre, and remained a soft-tosser, perhaps that success would have continued up the minor-league ladder. You won’t convince Cantillo it wouldn’t have. “I would put my 88 up against anyone else’s 98 and know I can compete with that,” he says. But he also recognizes one inherent truth of pitching — while there is no one way to collect outs, collecting them becomes a lot easier with each upward tick on the radar gun.

Despite his confidence in his 88-mph heater, Cantillo always wanted to throw harder. He’d drag his prep coach to the field seven days a week to train. He couldn’t help but compare his velocity to other Hawaiian high schoolers, even when he was throwing just 77 mph as a freshman. If he had to succeed living below 90 mph, his first two years in the pros had convinced him he could do it. But who wouldn’t want a little more?

In that sense, the trade to the Guardians has been a boon. Roughly four years ago, Cleveland began focusing on training velocity more intently, building out a program that touches players from all levels of the organization. (Bibee, one of the team’s top-100 prospects, is another beneficiary of that expertise.) Cantillo had landed in the right environment with the right tutors, and the Guardians had acquired the right pupil. Cantillo didn’t need to learn how to pitch — he’d proven he could — as much as he needed to learn how to throw hard. What’s more, he was eager to work both hard and smart. Cantillo is a learner, not a follower. He asks questions. “I like the fact that sometimes,” says Double-A pitching coach Owen Dew, “he’ll be like, ‘Why?’”

Due to an oblique injury that cost him most of 2021, Cantillo has spent more time in the pitching lab with the Guardians than on the field. But that allowed Cleveland’s host of pitching coaches — most notably pitching coordinators Ben Johnson and Joel Mangrum — to break down his delivery and build it back up again. Even as a prep player, Cantillo’s delivery reminded observers of Dodgers great Clayton Kershaw, and Cantillo admits to long admiring the future Hall of Famer. But his Kershaw emulation also left Cantillo’s delivery “a little herky-jerky,” as Baughman puts it. Once the Guardians got a look at him, there were some obvious areas to address.

Much of it involved the simple (or, to the layperson, not-so-simple) mechanics of throwing hard. For much of 2021 and into the following offseason, he focused on moving down the mound more quickly, to better generate momentum toward the plate. He accomplished that with the help of a tool called the Core Velocity Belt, which is basically a weightlifting belt with a bungee cord attached. That cord either sits in the hands of a coach or is staked to the ground, positioned so that it pulls against a pitcher throughout his delivery. The idea is to force the body to formulate its own response to that resistance, building new habits in the process.

To generate more force down the mound, Cantillo used the belt with the bungee staked in front of him, pulling him toward home plate faster than his body was prepared to move. Because that movement was happening whether Cantillo wanted it to or not, the exercise incentivized his body to organize itself in order to move that quickly. More force down the mound means more force into the ball, which means a faster fastball.

When Cantillo showed up at spring training last year, he hit 97 mph.

There is, of course, a downside to throwing in the mid-to-high 90s: The human body really isn’t meant to do it.

Cantillo started last season in Double A, his velocity settling in the 91-95 mph range. After just more than 60 innings of elite pitching, with a curve and a burgeoning cutter to go along with his spin rate fastball and deadly changeup, Cantillo’s shoulder started to hurt. He describes it as a combination of an impingement and shoulder soreness — nothing serious, but persistent. He tried to ramp back up many times after shutting down in early August, only for the issue to return. He didn’t pitch again the rest of the year, although Cleveland farm director Rob Cerfolio says Cantillo would have been able to make it back if he’d had anything left to prove at the level.

There’s a short and direct line to be drawn between his injury and his increased velocity, and Cantillo sees the connection as well as anybody. “My shoulder was always used to throwing 90 or 89 miles per hour,” he says. “This past season, I was throwing a lot harder.” But neither he nor the Guardians view his injury as a cautionary tale. Icarus may have flown too close to the sun, but Joey Cantillo just needs to fine-tune a few things.

Cantillo has spent most of his winter doing just that. He completed his rehabilitation in Cleveland, attending each of the Guardians’ home playoff games. (That includes the 15-inning walk-off win over the Yankees. “We were all standing there freezing,” he says.) Then he headed back to his idyllic home on Oahu. There, he spent plenty of time in the sand and in the surf, but he also worked out relentlessly to strengthen his scapula. If he was hurt because his body wasn’t used to throwing harder, he might as well help it get accustomed.

Cantillo also worked on his bracing pattern — how his lead leg locks as he lands on it mid-pitch, allowing him to transfer force from the ground up through his torso and into his arm — always looking for that extra tick or two. He knows there is more ground to be gained. “I didn’t average 100 miles an hour on my fastball last year. I didn’t average 95 on my fastball, either,” he says. “I want to throw harder this year.” The 97 mph he hit last spring was a flirtation, and Cantillo’s looking to go steady.

Cerfolio says the left-hander will enter spring competing for a rotation spot at Triple A, but Cantillo already has his gaze set on the big leagues. He has never lacked confidence. There may be several other Guardians pitchers in the system with bigger prospect pedigrees, not to mention a major-league rotation filled with pitchers who have yet to turn 30, but Cantillo is sure that he belongs among them. In the stands at Progressive Field last October, a sellout crowd thrumming around him, he was certain of it.

There is development left to come. Cantillo could stand to sharpen his command, and his non-changeup secondary pitches leave room for further refinement. Dew, his pitching coach last year, would like to see Cantillo throw his hardest fastball more often rather than saving it for tight spots. “In his two-strike fastballs, he can throw it harder,” the coach says. “I’m like, ‘Dude, do this 0-0.’” But the foundation is already there to succeed. In real estate parlance, the Padres acquired a house with good bones. Just wait until the remodel is done. “He has that background of having to get guys out at 88,” Dew says. What can he do at 98?

If Cantillo’s velocity gains continue apace, he may find out this coming season, perhaps even against major-league hitters. “I’m not really messing around this year,” he says. “I’m 23 this year. I’ve been trying to achieve this dream for a long time.” When he was a 16th-rounder throwing in the high 80s, achieving it would have seemed to most like a longshot. But then one of baseball’s best player development entities got his hands on him. Now, thanks in large part to the science of pitching development, envisioning that 16th-rounder in the major leagues hardly seems like a longshot at all.

(Photo: Mike Janes / Four Seam Images via Associated Press)